World War II has been the deadliest and most expensive war in the history of the world, costing the Allies alone north of 200,000 aircraft that were shot down in battle.

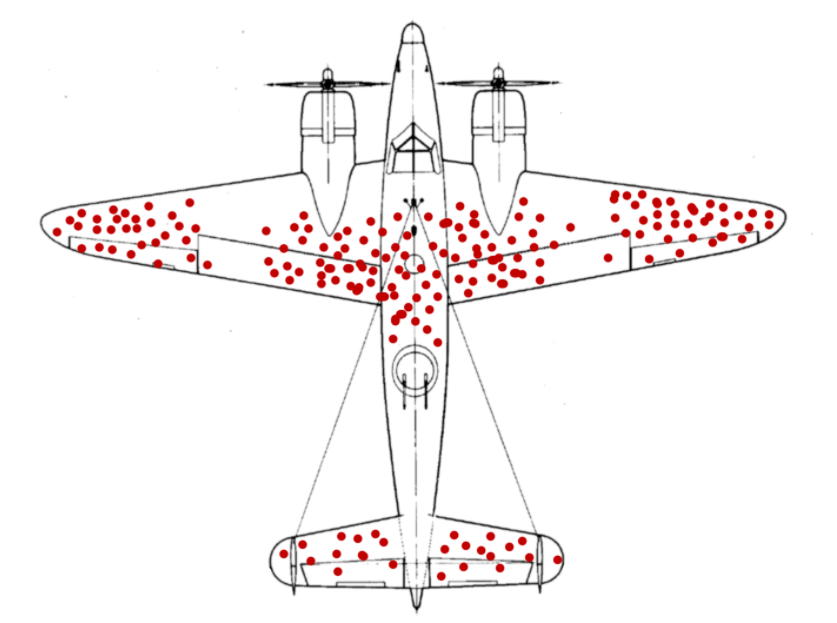

Unwilling to see their losses skyrocket even more than they already did, the US military, therefore, tasked a research team with examining all their the damaged bombers to identify if there is a particular damage pattern. They came up with the following map of the most-hit areas (red dots) and the areas that showed the least damage (white spaces):

Consequently, the US military concluded that those areas of the aircraft that got hit the most should be reinforced accordingly.

However, the statistician Abraham Wald had a different idea.

He suggested that the above map only shows the damage pattern of the planes that actually returned from battle. But what about the planes that got shot down? The US military obviously couldn't examine those, and so they didn't know their damage pattern, which is what they were actually interested in!

As a result, Wald approached the data from a different angle. Taking a look at the damage pattern of the planes that returned from battle, he realized that despite some areas being heavily damaged, they seemingly don't restrict the bombers' flight abilities and allowed the aircraft to return. But what about the areas that were not covered in bullet holes? What if these areas are actually the weak points of the bombers and that not being hit in these areas is what allowed the damaged planes to return in the first place, and that contrarily, those planes that did get hit in those areas, were the ones that got shot down?

Therefore, he suggested that instead of reinforcing the most-hit areas, the bombers' armor should be strengthened in the areas that showed the least damage as they are seemingly the weak points.

This idea was promptly put into practice and undoubtedly contributed towards the series of 1% improvements that compounded in the victory of the Allies.

What Wald and his team had achieved was to overcome one of the biggest hurdles within our thinking and decision-making abilities: Silent Evidence.

In simple terms, silent evidence is data that we don't have access to, like the damage patterns of shot-down planes.

The reasons for not having access to relevant data in that context could be that either the type of data we are seeking is pretty much unattainable (e.g. shot-down planes), however, it could also be our own inability to realize that this data exists in the first place.

Ever had that moment when you learn about something new that you can't believe you had never heard of before, leaving you in a state of complete surprise or even shock? I am sure we all have.

What these moments show us is that there are gaps in our knowledge that we are not even aware of. That there is information that we have never considered before because we didn't know it existed. Or in other words, that we don't know what we don't know.

And that's a significant problem. Why? Because it strongly limits our ability to draw up an accurate picture of the world, which is a prerequisite for making accurate predictions of the future and how our decisions affect the outcomes of certain situations.

To put it differently, silent evidence and our inability to recognize its existence distorts the truth.

But how can we be so oblivious?

Our brains try to make sense of the world every single second of the day. Most of the time subconsciously. And we can't control it. It's the reason why you can't stop yourself from reading words as soon as you see them and why you form a judgment about someone within the first 7 seconds of meeting them. Your brain is always on.

However, this constant interpretation and evaluation of our environment is a pretty exhausting activity. Hence, to save energy our brain has created "mental filters", which effectively act as shortcuts for making sense of any stimuli and information that we are bombarded with. Pretty smart.

The problem with this energy-efficient way of interpreting information is that our mental filters make us interpret the world in a way that confirms our beliefs, attitudes, and what we think we already know, creating biases along the way that help us make quick decisions. While this is great for saving energy and realizing quickly whether we are in an unfavorable or even dangerous situation and should take action quickly to correct it, these mechanisms make us oblivious to any silent evidence and create a distorted picture of the truth.

Consider what it takes to be successful for example.

We only ever hear the stories of successful entrepreneurs by the likes of Elon Musk, Bill Gates, or Steve Jobs and are conditioned to think that in order to be successful all it takes is a certain set of characteristics, hard work, resilience, and talent.

However, what we don't hear about are the entrepreneurs who had the same characteristics, who were equally hard-working, resilient, and talented but who failed miserably.

Some of the great thinkers of our times like Nassim Nichola Taleb or Malcolm Gladwell have highlighted on numerous occasions that success is a far more complex domain including uncontrollable elements like luck, coincidence, opportunism, a favorable background, or access to a rare set of opportunities, all of which are crucial factors that made Bill Gates rich and whose lack thereof drove other entrepreneurs into bankruptcy.

Unfortunately, we only ever hear one side of the story. The untold stories of the thousands of people who on the surface should have had the same success as Bill Gates are the silent evidence that distorts the true picture of what it takes to be "successful".

Lastly, consider a rather provocative story from Cicero, which Nassim Nicholas Taleb recites in his book The Black Swan to show that silent evidence is even a reason to question the perceived power of religious belief:

"Diagoras, a nonbeliever in the gods, was shown painted tablets bearing the portraits of some worshippers who prayed, then survived a subsequent shipwreck. The implication was that praying protects you from drowning."

"Diagoras asked, “Where are the pictures of those who prayed, then drowned?"

I guess we'll never be able to hear their story. They might be the silent evidence that praying brings no protection after all.

The question is obviously how can we overcome silent evidence? How can we, like Wald and his team, overcome our natural inability to realize that silent evidence might exist in the first place even if we can't access it?

Here are my suggestions:

As so often, the first step on the ladder to overcoming silent evidence is to become aware that silent evidence exists. Accept that you don't know what you don't know. Especially in today's environment, it is impossible to have access to all the relevant information and knowing what information is relevant in the first place. Whether you are forecasting the budget for your next project or predicting demand for your new product. Whether you are analyzing the cause of the latest stock market crash or the performance of your favorite football team. Our world is far more complex than we can capture and thus there will always be silent evidence somewhere.

Hence, always include an error rate within all the calculations and decisions you are making to create a better indication of how confident you are in the information you have gathered or whether you see the potential for highly impactful silent evidence.

Secondly, we have to find ways to challenge our mental mechanism to interpret information in a way that confirms our biases.

To do so, we have to look for counterarguments that disconfirm our perceptions.

This practice is particularly common amongst the most successful stock market investors like Warren Buffet. When they analyze an attractive company that they are considering investing in, they try to prevent themselves from falling in love with the stock and filtering out all the information that makes the company seem like a really attractive investment company and instead focus on what they don't like about it. This way they force themselves to do a sort of research, which leads them to discover any silent evidence that they wouldn't have necessarily considered before, enabling them to generate a much more accurate and objective picture of the investement opportunity.

Seeking disconfirmations may feel a bit uncomfortable because we are basically trying to prove ourselves and our beliefs wrong. However, through frequent practice, this will turn us into better decision-makers, which will positively affect all aspects of our life, be it work, relationships, or our general happiness.

Related to seeking disconfirmation is my final suggestion for overcoming silent evidence: Reflective Skepticism.

In essence, reflective skepticism is about questioning your assumptions, perspective, and the information you have gathered to prevent yourself from merely confirming your own biases and to determine whether there are any unknown unknowns that have not been considered which however are crucial to revealing the whole truth. The questions to ask yourself are:

Follow these steps and you will soon look at your damage patterns from the right perspective.

My Story

My name is Stefan, and just like you, I had (and still have) this little voice in my head telling me that I'm not good enough.... continue reading

More blog posts

What everyone ought to know about boosting your self-esteem.

(Do not carry on with your self-affirmations if you truly want to feel confident again.)

Discover what the real 'currencies of self-esteem' are and how to amass them like weeds.